The making of the calendar

All over the world, humans from as early as the Bronze age have been observing and recording nature’s cycles, and with it have created systems to organize time. Today you’d call this system a calendar.

Calendars were not uniform across the world. The South Americans had their own calendar. The ancient Egyptians had theirs too. So did the ancient Chinese and the Sumerians. Each of these calendars were calculated differently and readjusted at different rates, but they all have one thing in common:

- They are all based on observing the cycles in the sky.

Observing the sun, moon and seasons

The cycles in nature are clear – but some more clear than others.

It was universally easier to observe what a day consists of – a period of light and of darkness – or of sun and moon. Changes of seasons are also very noticeable, especially in temperate regions which are places that have more than one season.

Some cycles required keener observation. For example, the cycle of the moon shape.

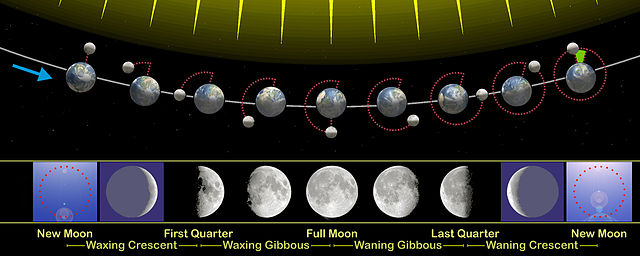

Humanity has realized that the moon wax and wanes. In other words, the moon cycles through phases. For example: It begins at the appearance of its crescent – which we call a new moon and returns to that same shape again. Or (or!), it begins as a full moon , then undergoes a series of transformations to return to its full state again.

You might think that it’s the same thing, but this arbitrary starting point makes all the difference between one people’s calendar and another. Nonetheless, one full cycle of these moon phases is called a lunation and takes on average 29.5 days. Months are based on these cycles. In fact, the word ‘month’ is a cognate of the word ‘moon’. And our ancestors use these to create calendars, which we call lunar calendars because they are based on the cycle of the moon.

While some civilizations, such as the Mayans, already followed a solar calendar from the get go, albeit flawed, most of the ancient world began with lunar calendars and eventually transitioned to a solar calendar – meaning that they would be based on the sun’s 365 day orbit. As mentioned earlier, depending on regions, calendars evolved differently and at different rate. Because our current calendar – the one most of the world follows – evolved from that of ancient Rome, we’ll learn about the Roman calendar trajectory.

Evolution of the ancient Roman calendar (to today’s)

Traditions say that the earliest known Roman calendar only had 10 months, beginning with March (when the Spring equinox occurs) and ending with December. It’s suggested that this calendar was meant for agriculture purposes and because there was no work during winter season, those days were not given months.

According to ancient Roman sources, in ~ 738 B.C.E. King Numa Pompilous added two more months, January and February, in order to align the 12 lunar months with the solar cycle. This resulted in a year that had 354 days. That’s still 10 days short of the time it takes for earth to orbit around the sun – which was determined to be 365 days and 6 hours. This would eventually cause a discrepancy over time.

By 46 B.C., it became clear that the seasons were not aligning with the calendar year. As a result, Julius Caesar, on the advisory of the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes, implemented another reform; Not only were certain months lengthened to make up for the discrepancy, but a leap year was introduced every four years to realign with the solar year. This new calendar was named after the general and referred to as the Julian calendar. Additionally, his birth month then called Quintilis, was renamed to “July” in his honor.

Around this time (some sources say that it was in 153 B.C), the Roman calendar changed the new year start from the month of March to January – mostly for practical reasons, as the newly elected Roman council would resume office in January. Besides, January which corresponds to the God Janus – the god of Gates, beginnings and endings – seemed to be a fitting choice for the beginning of the year (all about the 12 months and their name origins here). Although the year now begins with January, it’s worth noting that in some cultures, such as the Persian culture, the new year begins on the spring equinox.

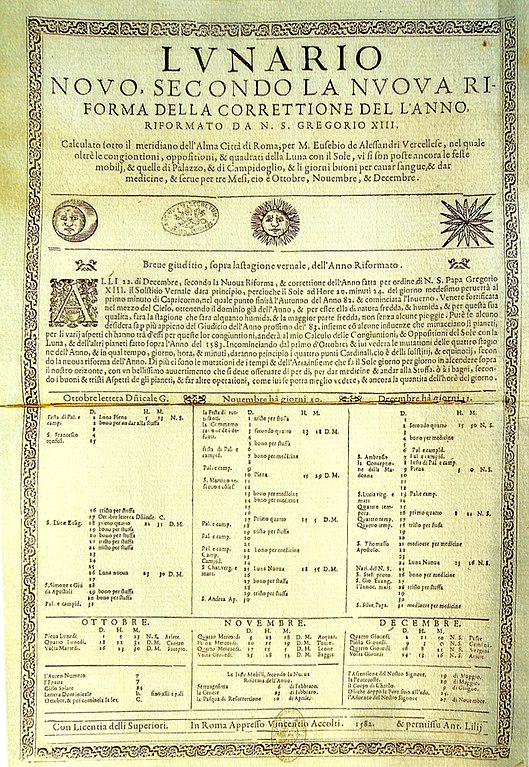

In 1582, over 15 centuries later, the Julian calendar underwent a reform led by Pope Gregory Xlll whose astronomer, Christopher Clavius, figured out that the solar year was not 365 yrs and 6 hours, but that it was actually 365 days , 5 hours, 48 minutes and 46 seconds! This may not seem significant , but if you do the math, being ahead by 11 minutes adds up over time. The solution was to eliminate three leap years every 4 centuries.

This reformed calendar is called the Gregorian calendar and is the one we still use today. It’s come a long way through various reforms due to increasingly advanced observations of the sky. Which makes you wonder, “will we find something else and require another reform? Well in the 20th c. we actually did find something, though not so urgent for many generations to come; its’ that we would need to add one day every 3,323 years!

What about the 7-day week?

Now, that we understand that the day, month and year was formed progressively through the observation of sun and the moon’s cycle, let’s move on to the week. How was it created, if not following any clear cycle? And could the names of each day of the week give us a clue?

First we need to understand why the notion of a week was even required, because they did exist all across the world, and they came in different numbers:

- African tribes had a 10 day-week

- The Ancient Chinese had 5-day weeks which extended to 10-days

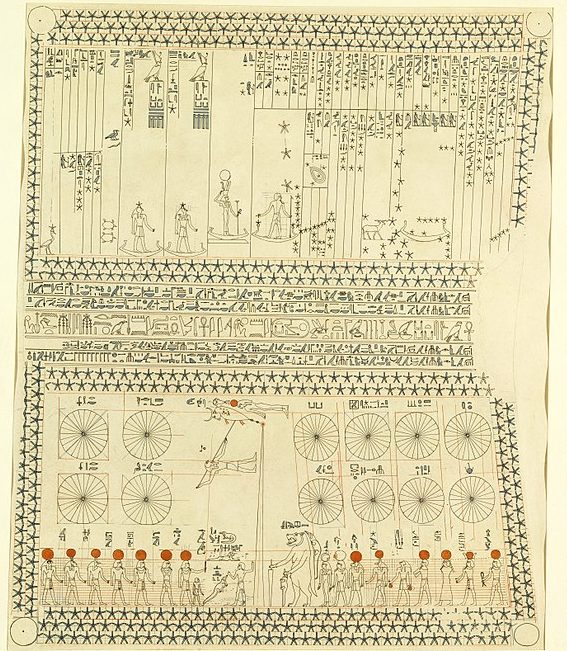

- Ancient Egyptians had a 10-day week

- The Aztek and Mayas had a 13-day week

- Icelandic, Javanese, Koreans had 5-day week

- And France once had a 10-day week

It’s believed that weeks were meant to further break up the days in the trading world; to provide a routine and a period of rest; for example, the ancient Chinese Confucian civil service set the 5th day to be a bath day. I could see why we would choose the arbitrary 10 or 5, because of our 10 fingers or 5 fingers. But 7 is an odd number. So why did we settle for 7?

A very popular theory is that the number 7 was chosen due to its biblical sacredness. The first chapter of Genesis talks about a 7-day creation, that God took 6 days to create the world and rested on the 7th day. The number 7 represented completion and divine perfection and is mentioned in other parts of the bible.

“Seven priests shall bear seven trumpets of rams’ horns before the ark. On the seventh day you shall march around the city seven times, and the priests shall blow trumpets” – Joshua 6:3-4

But where did the bible get this number 7 from?

Some say that there are no other inspirations. But I can’t help but to think of a couple of ancient Mesopotamian texts, written before the bible and in the surrounding region. One is the Enuma Elish, an ancient Babylonian myth that talks about the creation of the world and that’s recorded in 7 tablets.

The other is the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest religious texts and literature, which talks about a deadly flood that lasted 7 days and that is hero Utnapishtim sent out a dove 7 days later. There are many other references to the sacred number 7, such as the baking of bread and only the 7th was perfect, as well as the “7 sages”. The ancient Mesopotamian clearly venerated the number 7.

In fact the Babylonian calendar is the earliest found calendar that contained 7-day weeks. Their calendar contained 12 lunar months and they celebrated the 7th day from each new moon, as well as the 14th, 21st and 28th. These days were considered holy in which activities were prohibited…which is very similar to the Jewish Sabbath.

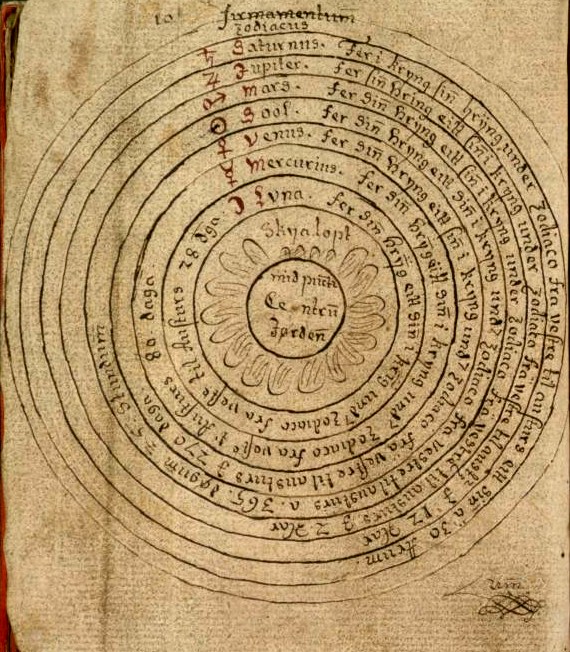

The reason for this 7-day segment could have been to divide the lunar phases into 4 parts, creating an average 7-day week. However records show that the Babylonians who were very keen on astronomy, had recognized 7 moving bright objects in the sky, which they named after gods. Samas, Sin, Nabu, Istar, Nergal, Marduk, and Ninib. These moving bodies that can be seen with the naked eye are what we now know as the sun, moon, mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Today, we call these “the classical planets” (even though they are not all planets).

The names of these Babylonian gods were also used to name their 7 days of the week. Fast forward 4000 years, and not much has changed. We still name our 7-day week after these gods.

In Roman-derived languages such as French or Spanish, most of the days are named after the Roman-equivalent of these gods . Let’s take French.

- Lundi is named after Luna

- Mardi after the god Mars

- Mercredi after Mercury

- Jeudi after Jupiter

- Vendredi after Venus

- Samedi though, is believed to come from the Jewish Sabbath

- Dimanche comes from Latin term Dies Dominica, which means the Day of the Lord

In Germanic derived languages such as English, many of the week’s days are named after the Germanic-equivalent of these gods.

- Monday comes from the moon’s day (god Mani)

- Tuesday from Tir’s day

- Wednesday from Woden’s day

- Thursday from Thor’s day

- Friday from Frigg’s day

- Saturday, for some reason uses the Roman god Saturn (Saturn’s day)

- Sunday from the sun’s day

The conversion from the Babylonian week to the Roman week was not straightforward. The Romans didn’t have a 7-day week until the 4th CE. Prior to that, they had an 8-day week. It’s believed that the Romans adopted the implementation of the classical planets into their time, from the Greeks ,who themselves adopted from the ancient Mesopotamians.

And this my friends, is believed to be the reason our week is comprised of 7 days – named after the sun, the moon, and the 5 closest planets which were visible to our ancient ancestors’ eyes.

Based on this theory, it’s funny to think that the number 7 hinged purely on our ability and limits to see the planets. Had our ancestors observed a different number of bright moving objects, would the length of our week be different?