The Yin Yang, also written ‘Yinyang’ or Yin-Yang, is an ancient symbol based on Chinese philosophy, but how exactly did it come about? What is the true meaning behind it? Does it mean Good vs. Bad? We’ll get to the bottom of this, but first I need to stress that the information will be highly condensed. The Yinyang history and applications are ginormous, so I will be sharing the key points, in the most simplistic way possible.

The Yin Yang Symbol Evolved Through a Series of Diagrams

Intellectuals of ancient China practiced an art called Xiang or Tu, the art of diagram or image-making. The art consisted of numerical representations, text and shapes, with the goal of communicating the patterns of the universe according to the vision of the Yijing.

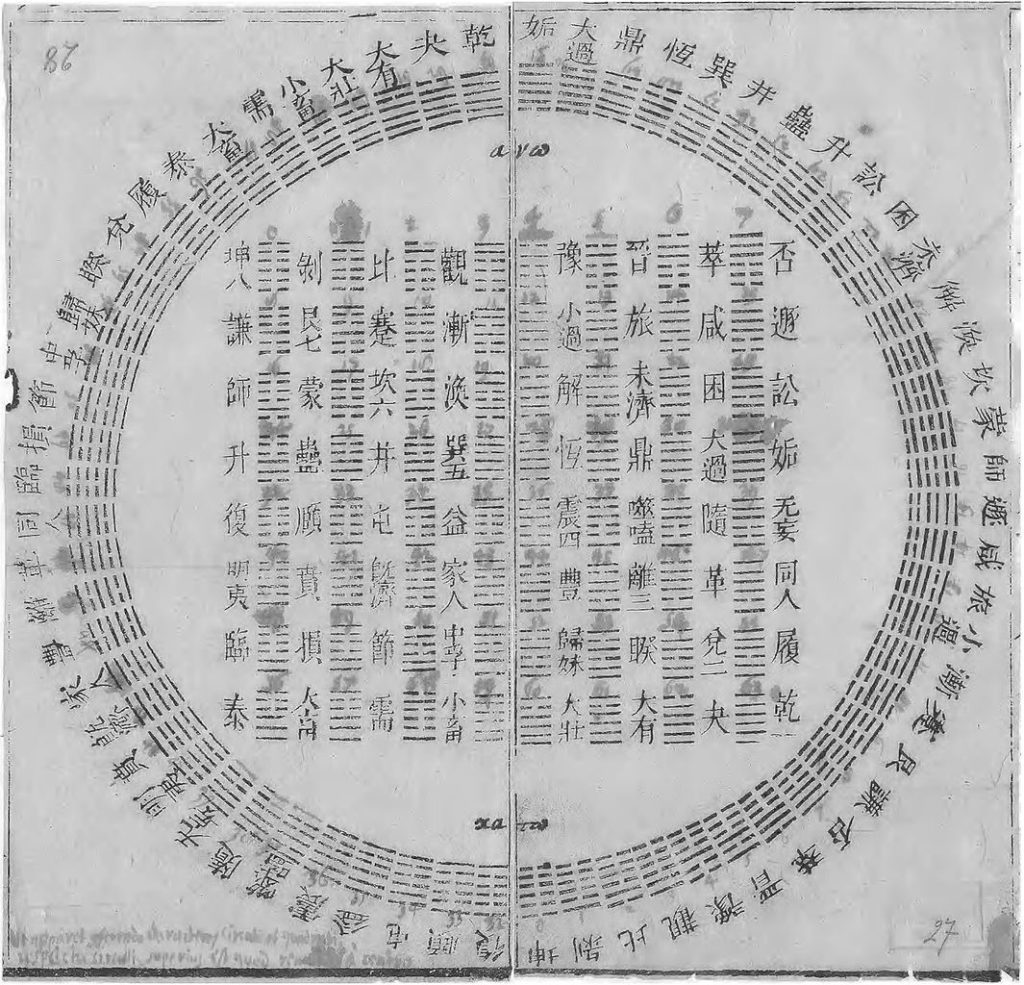

The Yijing (or I Ching) is a divination text based on changes and transformation. It’s the oldest living classic of China and the precursor of most Chinese philosophy and culture. The Yijing is basically a manual that provides advice to any specific question one may have. The text centres around 64 hexagrams, made of yin and yang lines, designed to cover all the structures of being and possible changes.

The hexagram is dynamic. They each mean something, and so does each of its lines. When one line changes from yin to yang or yang to yin, the entire hexagram changes, as well as the interpretation.

Diagram Yijing (I Ching) hexagrams

The Yijing reflects the ancient Chinese thought that everything becomes and transforms… from yin to yang and yang to yin.

What is Yin and what is Yang?

YinYang (Yin Yang) started off as two separate terms to describe geographic places in relation to the sun. The sunny and warm side of the mountain was called Yang. And the cold and shady side was called Yin. This led to the classification of everything that exists as a yin or a yang element. But there is a system…

Yin is dark, cold, empty, passive, submissive, hidden, still, soft, the water, the moon, the earth, and the feminine.

Yang is the opposite of yin; Yang is bright, warm, full, active, dominating, visible, moving, hard, fire, the sun, the heavens and masculine. The list goes on…

Basically, everything in the world is either yin or yang, and because yin essentially represents the female and yang the male, things are either of female attribute or of male attribute. The Yinyang philosophy fundamentally takes after male and female biological differences and interactions.

As female and male are opposites, they are also complimentary. The same goes for the yin and yang. The ancient Chinese thinkers saw that there is a paradoxical interdependence on everything that appeared to be opposites. Brightness can only exist with darkness. They interact with each other and make the world function. Day and Night mark the rotation of the earth on its axis. Male and female procreate.

From the naming of the mountainside, Yinyang became a way of thinking. The Yinyang thought was a way of seeing the universe. So how did the ancient Chinese see the cosmos?

Pangu or the Origins of the Universe

A popular Chinese creation myth tells how before everything, there was formless chaos, no light not darkness, and it took the form of a cosmic egg. For thousands of years, Pangu the hero was sleeping it. During that time, the forces of yin and yang became balanced.

When Pangu woke up, he cracked the egg open and separated the yang from the yin. He extended the heavens upwards, and the earth downwards, all the while growing longer. Thousands of years later, heaven and earth reached their maximum height and depth. Pangu couldn’t grow anymore, so he died and all his body parts became all the parts of the universe, the ‘ten thousand things’. His breath became the winds and the clouds, his left eye the sun, his right eye the moon, his blood the ocean and rivers, his facial hair the stars and milky way, and so on and so forth.

There are different versions of this myth but overall, it reflects the logic and patterns of the universe according to other Ancient Chinese texts.

The Dao and the Qi

Early Chinese philosophers believed that the universe originated from an ultimate source. They called it the Dao or the Great one. The Dao contains the Yinyang, which is like the fabric of the universe. It’s the net that’s embedded in all things. Through the functions of the Yingyang net, travels the Qi, a life force that animates everything that exists.

The ultimate Dao is like Pangu’s egg. These two also parallel what we call today the ‘nothingness with full potentiality’, which can be symbolized by the dot, ‘0’ or the circle.

Pangu’s body becoming the parts of the universe also reflects the ancient Chinese idea that the cosmos and the human body share the same anatomical map. In this vision, the universe is conceived as a living organism paralleling the human body in terms of rhythm, functions and movements.

Humans, the earth and the cosmos all affect each other through the system of Yin and Yang. For example. When the Yang-sun comes out, the people go out on the rice fields and are active, and ‘activity’ is also a Yang element. When the Yin-moon appears, it’s time for rest, which is a Yin state. It was also believed that human activity affected the broader cosmos. What the humans did on earth could cause cosmic reactions, like rain or drought.

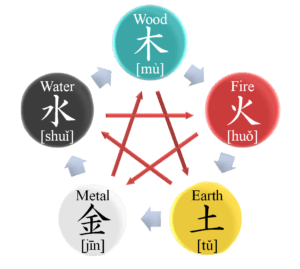

The Five Phase Theory

A theory that was not reflected in the Pangu mythology but essential to the Yinyang thought is the Wu-Xing or the 5-phase theory. Basically it’s the interaction sequences between nature’s 5 elements; fire, water, earth, wood and metal. For example, water overcomes fire, fire overcomes metal, and so on.

Five Phase Theory

Five Phase Theory

This theory suggests that other objects or states also correspond to the 5 elements and share the same sequence of interaction. According to the Wu Xing, salty taste overcomes bitter taste.

RECAP

Few! Let’s do a quick recap on the general Yin Yang thought we’ve covered so far.

- The ancient Chinese saw the universe as being governed by two opposing but equal and complementary forces which act as a mechanism for the Qi, the life force that animates everything.

- The cosmos and humans are connected and share the same anatomical structure.

- Life’s elements interact in accordance with the 5 phase-theory.

But hold on now! The Yin Yang thought was more than a way of seeing the world!

To the Chinese sages, all aspects of life are like a universe of their own, they are all subject to the Yin Yang theory. They believed that if you can understand this well, you will see that the Yin Yang theory can be used as a type of blueprint for doing things, the “right way”.

This efficient way of doing something is called Shu, or strategies. And Shu’s are guided by the Yinyang principles.

There is a Shu for everything; for battle, for sex, for living arrangement, for combat, for music, art, political affairs, and for medicine. Medical based Shu’s have had a major influence in broadening and systemizing the meaning of Yin Yang.

Yinyang was a way of seeing the world and a way of life

Essentially, Yin yang was everything. No wonder the Chinese thinkers had to put it on paper… But text is discursive and had its limits, so the Chinese designed images and diagrams. They looked quite complicated, but remember that they weren’t meant for aesthetics, but for explaining the complex patterns of the universe. Lots were created, but there were 3 main trends of Chinese image-making.

The Three Trends

- Hetu and Luosho

- Eight trigrams

- Taijitu.

These three had significant connections with one another and were all essentially derived from the Yijing. Let’s look at each of the trends.

1) Hetu and Luoshu

The Hetu and Luoshu, symbolizing heaven and earth respectively, each show mathematical patterns representing the generative forces of the universe through the balance of yin and yang.

An 11th-century commentator of the Yijing drew these charts inspired by what had been seen on the back of a tortoise and a dragon-like horse, in the river.

The black dots which are grouped to form even numbers are Yin. These numbers represent completion.

The white dots which are grouped to form odd numbers are yang. These numbers represent generation.

For example, in the Hetu chart which represents numbers 1-10, the total sum of even numbers on top and bottom is equal to the total sum of odd numbers on top and bottom.

The Luoshu diagram, which represents the numbers 1-9, shows the importance of the number 9. If these groups of dots were replaced by the corresponding number, it would form the magic square of 3. The sums of any column, row or diagonal equals 15.

2) The Eight Trigrams

The second trend is the two sets of eight trigrams taken from the Yijing, and represent its concepts, revealing the basic cyclic and polar forces of the universe.

The circular positioning of the trigrams set a precedence in the Yin Yang Xiang making because it shows the cosmological cyclical patterns of rise and decline. As you go around the circle, you can see the waxing and waning of yin and yang.

3) Taijitu

The 3rd trend of image-making is the Taijitu. It consists of 5 steps, read from top to bottom, to explain the movement from a unitary (one) source into a diversified world.

First, there’s the absolute void, then the yin and yang complementary duality, then the wu xing theory and then eventually everything, which becomes and transforms.

In the 14th century, these three trends were combined to form the prototype for the Yinyang symbol.

The artist who made it called it a Hetu (river diagram) just like the one from the 1st trend.

It took the circular shape and trigrams from the Eight Trigrams diagram and it contains the Yin Yang halves from the Taijitu sequence, only, it’s evolved into an interlocking of swirling Yin Yang halves.

And from there, came different renditions which look more and more like the modern symbol we know today.

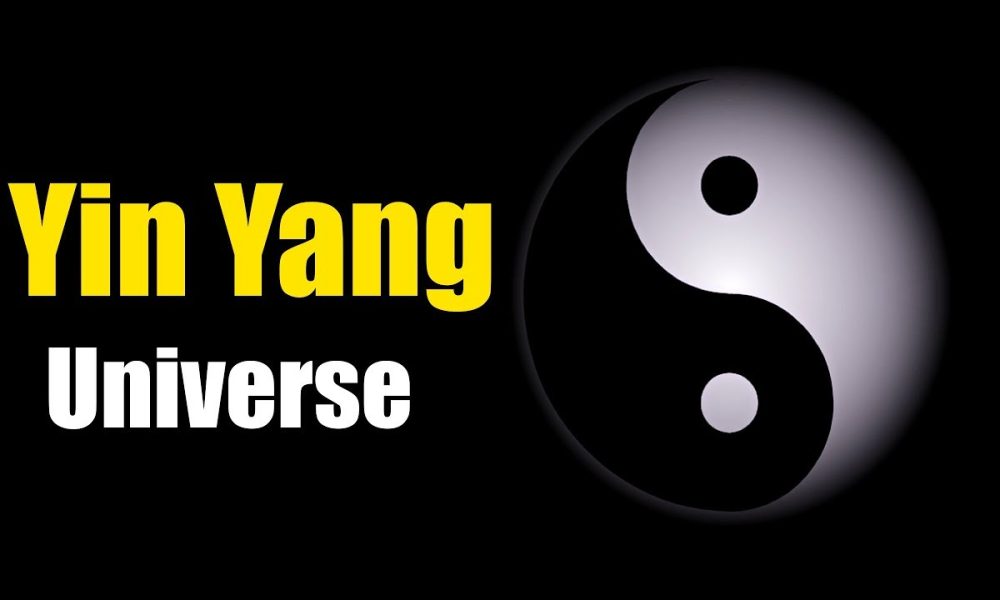

Dissecting the Yin Yang Symbol

Ok, let’s go over some of the cosmological patterns that the symbol shows:

- The world or the whole is fundamentally made of, and governed by two opposite forces, yin and yang.

- At any point in time and place, there is both yin and yang. This could be seen by drawing a line from the centre of the circle to any of its peripheries. (and only seen in the earlier version of the Yinyang)

- The equal proportion of each opposite shows that they are of equal importance and complimentary. One cannot exist without the other.

- The intertwining and swirling of the two represent the self-created and ongoing cycle of these opposites. One transforms into the other. In the strong moment of yang, there is a seed of yin. And Yin will begin. And in the strong moment of yin, there is a seed of yang. And this cycle keeps going.

- The swirling also represents movement. At any point, yin or yang is in the process of changing. Things are always transforming. One way or the other.

- Yin and yang form a circle, which can symbolize heaven, a whole, or an entity.

- The whole made up of the interaction of 2 forces also represents threeness, a very important element in the Yin Yang thought. The whole is larger than the sum of its parts. Yinyang creates a new existence.

The Dao generates oneness, oneness generates twoness, twoness generates Threeness and Threeness generates the myriad things

Today’s modern Yin Yang symbol changed a bit. It lost some informative details, but still maintains the core ideas of the more ancient symbols. It’s unknown who created it and when, but we can see that endless variations have been created by all types of individuals across the world.

The Yin Yang has become a universal symbol and is mostly known to represent the harmony of dualism, especially between good and bad. But as we’ve seen, the Ancient Chinese intellectuals never meant it to represent good and bad (although the rules could apply there too). They meant to create an image that represents much more than just the balance of opposites.

The Yin Yang symbol is derived from a rich history of image-making in order to express a complex way of thinking. And remember; we’ve just scratched the surface.

Yinyang is a way of seeing the world; one that came from an ultimate source of nothingness; a world governed by two opposing yet complementary forces that control the energy that animates all things; a world in constant transformation; a world subject to cycles of rise and decline, and to the theory of 5 phases; a world that we can find above us, around us and within us.

Sources

Books and Further Reading

- Wang, Robin R. (2012) YINYANG – The Way of Heaven and Earth in Chinese Thought and Culture. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press

- Farnell, Kim (2017) I CHING – Plain & Simple. Charlottesville, VA: Hampton Roads Publishing Company

Websites

Pangu Creation Mythology

– https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pangu

– https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_creation_myths

Yinyang term – https://www.iep.utm.edu/yinyang/

Wu Xing – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wu_Xing

Images

Wu Xing – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wu_Xing

Ancient Yinyang symbols – https://www.biroco.com/yijing/louis_taiji_diagram.pdf

Public Domain Images

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Public_domain_image_resources

Video – Creative Commons

Yin Yang fractals – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xXrNIx8c4As

Egg fertilizing – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tdMEbvuJ49M

Night and Day explanation – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hWkKSkI3gkU&t=179s