Brief overview of Dionysus

Initially worshipped as a god of vegetation and fertility, Dionysus later became known for theater, and most famously, as the god of wine, ecstasy, and festivity. His foreign origins are an essential part of his myth, and in Rome, he was also known as Bacchus, a name adopted by the Greeks as one of his epithets.

Dionysus in ancient Greek society

Dionysus was one of the most important deities in ancient Greek religion. His worship dates back to at least the 13th century BC, as evidenced by newly discovered Linear B tablets from the Mycenaean period. Initially, Dionysus was a god of vegetation and fertility, but his traits and associations evolved over time:

- 6th c. BC: In Athens, Dionysus became the god of theater, with festivals celebrating theatrical performances, including tragedies and comedies.

- Classical Period (5th-4th c. BC): He became associated with ecstasy, ritual madness, and liberation from social constraints.

- Hellenistic Period (4th-1st c. BC): Dionysus was tied to mystery cults, such as the Orphic mysteries, which emphasized death and rebirth.

Throughout all these changes, Dionysus retained a strong association with being a foreign god, arriving in Greece from Thrace or Asia Minor. His connection to wine is likely tied to the importance of viticulture in Greek society, and is his most enduring association.

The festivals associated with Dionysus

Dionysia: A major festival that honored Dionysus with theatrical performances, particularly tragedies and comedies. This festival was the second most important in Athens after the Panathenaea and consisted of two separate celebrations: the City Dionysia and the Rural Dionysia, beginning in the 6th century BC. (The first drama competition in Athens took place in 534 BCE as part of this festival.)

Anthesteria: This festival celebrating the opening of last year’s vintage, and involved feasts and an inversion of social order, allowing slaves and other marginalized groups to participate. It also included rituals for the dead and was celebrated in Athens and Ionian cities around late February or early March, dating back to the 10th or 11th century BC.

Lenaia: A lesser-known festival for dramatic performances, honouring Dionysus’s rebirth after being dismembered by the Titans and had strong ties to wine-making. It was celebrated from the 5th century BC to at least the 2nd century, in Athens and Ionian cities

Cults and rituals

Orphism: A spiritual movement that revered Dionysus (and Persephone) and their connection to the underworld, focusing on themes of death, rebirth, and spiritual purification. The myth of Dionysus’s dismemberment at the hands of the Titans was Central to Orphism, as it symbolizes death and resurrection. (a concepts that likely influenced Christianity)

Dionysian/Bacchic Mysteries: These religious rituals often involved wine and other intoxicants, as well as trance-inducing dances meant to free participants from societal constraints and personal inhibitions. The rites, which appealed particularly to marginalized groups (such as slaves, women, and foreigners), were practiced in both Greece and Rome, though their exact origins remain debated. They are famously depicted in the Bacchanals of the Maenads.

Bacchanalia: emerged in Rome around 2nd c. BC as an unofficial mystery cult derived from the Greek Dionysian festivals. These secretive rites involved ecstatic revelry, intoxication, and the worship of Bacchus (the Roman name for Dionysus) and Liber (another association)

Notable authors who wrote about Dionysus

Homer (8th c. BC, poet): In Homeric Hymn to Dionysus (1, 7), he talks about:

- Mount Nysa as a place far from Phoenicia, near the Egyptian stream.

- Dionysus’s kidnapping by sailors who thought he was a prince and wanted to ransom him. Dionysus turned into a lion and unleashed bears to demonstrate his divinity.

Euripides (5th c. BC, playwright): In The Bacchae, he talks about:

- King Pentheus denying the divinity of his cousin Dionysus and being brutally attacked by maenads.

Herodotus (5th c. BC, historian): In Histories, he talks about:

- Dionysus being carried in Zeus’s thigh and taken to Nysa, located beyond Egypt in Ethiopia.

Pseudo-Apollodorus (2nd c. BC, mythographer): In Bibliotheca, he talks about:

- Dionysus traveling the world, opposing those who denied his godhood.

- The story of Dionysus on a ship with sailors.

- His descent to the underworld and renaming his mother Thyone.

Diodorus (1st c. BC, historian): In Bibliotheca Historia, he talks about:

- The three incarnations of Dionysus.

- Dionysus teaching mortals to use oxen to plow the fields instead of by hand.

- His dismemberment and rebirth.

- Dionysus as the son of Ammon and Amaltheia via an affair. Ammon, who was married to Rhea, hid Dionysus out of fear of her wrath by sending the baby to Nysa. There, Dionysus grew up skilled, strong, and learned the art of winemaking.

- Dionysus was one of Centaur Chiron’s pupils.

- His descent to the underworld to retrieve his mother.

Hyginus (1st c. AD, Latin author): In Fabulae, he talks about:

- Dionysus’s double birth.

- Dionysus (Liber), first born as the son of Zeus and Persephone. After being torn apart by the Titans, Zeus collected the remains and gave them to Semele, who drank them and became pregnant again with Dionysus.

Pausanias (2nd c. AD, geographer): In Description of Greece, he talks about:

- Two different versions of Dionysus’s descent into the underworld (katabasis) to retrieve his mother.

Nonnus (5th c. AD, poet): In Dionysiaca, he talks about:

- The three incarnations of Dionysus, focusing on his birth to Zeus and Semele.

- “Where his limbs had been cut piecemeal by the Titan steel, the end of his life was the beginning of a new life as Dionysos.”

- After the flood, Zeus sent Dionysus to teach mortals about wine to alleviate their suffering.

- Semele had a prophetic dream of a tree struck by lightning that spared the fruit, symbolizing her and Dionysus.

- The birth of Dionysus is seen as an allegory for the regenerative forces of nature, with his dismemberment symbolizing the wine-making process. (Dionysus was born from the gods of rain and earth. He was torn apart and boiled by the sons of Gaia (the “earth-born”), symbolizing the harvesting and wine-making process. Just as the remains of bare vines are returned to produce wine, the remains of the young Dionysus were returned allowing him to be born again)

Core mythological narratives of Dionysus

Dionysus had what various authors call different incarnations or manifestations of Dionysus.

Dionysus’ first birth (Zeus & Persephone)

Dionysus, also known as Zagreus, was the son of Zeus and Persephone (sometimes Demeter). Born with horns and showing signs of great power, he was destined to succeed Zeus. However, Hera, jealous of his power, sent the Titans to dismember and kill him. (His pieces would later be collected, and Dionysus would be reborn (Diodorus).

Dionysus’ second birth: of a god and a mortal (the more popular story today)

Mortal princess Semele was pregnant by Zeus, and was told that her future son would be divine, but Hera – Zeus’ wife – was jealous and tricked Semele into asking Zeus to reveal his full godly form, aware of the consequences. Semele did, and was burned from the intensity of Zeus’s presence. Zeus was able to save the unborn baby and sewed him in his thigh until his rebirth.

Growing up and spreading viticulture far and wide

After Dionysus’s second birth, Zeus entrusted his care to different figures, depending on the version of the myth. In some, Hermes passed him around and ultimately to goddess Rhea, while in others, he was raised by the rain-nymphs of Nysa. Dionysus grew skilled, mastering arts, religious rites, and viticulture (winemaking).

He then started to travel. In a version, Hera’s curse drove him mad, causing him to wander until Rhea cured him. After learning religious rites, he traveled towards Asia, teaching winemaking, an invention credited to him, and stayed in India for several years.

Return to Greece and Triumphant

Dionysus returned to Greece triumphant after his travels through Asia. Wherever he went, he established his cult and faced resistance from those who rejected his divinity, fearing the madness and disorder his worship invoked. Dionysus had to defend his godhood from skeptics.

Punishment for denying his divinity

Pentheus – Dionysus returned to his birthplace Thebes, ruled by his cousin Pentheus. Pentheus, along with his mother and aunts, denied Dionysus’s divinity, accusing him of inspiring madness in Theban women. Dionysus turned Pentheus mad, driving him to spy on maenads, which included his mother and aunt, during their ecstatic rituals. When the maenads spotted him, they tore him apart. Dionysus punishes all those who denied him. The only one spared was the blind prophet Tiresias, who warned Pentheus and his mother.

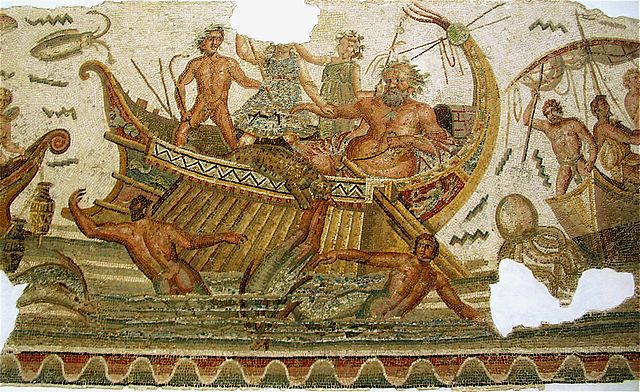

Pirate ship – Dionysus was kidnapped by sailors, so he revealed his divine powers, turning into a lion and unleashing a bear, killing everyone on his path. Those who survived jumped overboard and were turned into dolphins. Only Acoetes, who recognized Dionysus’s divinity, was spared. In another version, Dionysus turned the mast and oars into snakes, filled the ship with ivy, and drove the sailors mad, causing them to leap into the sea and become dolphins.

Descent to the underworld to retrieve his mother

Dionysus descended to the underworld to rescue his mother, Semele, and make her a goddess among the Olympians. They both emerged from a lagoon, though sources differ on the exact location. In one version, he renamed her Thyone.

This myth may have come about because when Dionysus became one of the most important Greek gods, even though she was mortal, many would deify his mother after her death. This concept echoes the debates over the Virgin Mary’s divinity, contributing to the division between Christianity and Catholicism.

Other myths:

Midas’s wish

Silenus, Dionysus’s tutor and foster father, wandered off and went missing, only to be taken in by King Midas for 10 days. Grateful, Dionysus offered to grant Midas any wish. Midas wished that everything he touched would turn to gold. This wish, however, soon backfired when his food, and even his daughter, turned into gold. After being prayed to for help, he reverse the curse by instructing him to wash in the river Pactolus, which then turned into gold (hence the gold sand).

Ariadne

Dionysus discovered Ariadne on the shores of Naxos after she had been abandoned by her new husband, Theseus, whom she had helped escape the minotaur’s labyrinth. In one version, Dionysus, captivated by her beauty and compassion, consoled and married her, eventually making her immortal and placing her crown among the stars as the constellation Corona Borealis. In some versions, Dionysus deified her in different ways. In another version, Dionysus himself ordered Theseus to abandon Ariadne so that he could marry her.

Epithets of Dionysus

Dionysus is known by around 66 epithets. Some of the most important include:

- Bacchus (or Iacchus): One of his most common epithets, linked to the frenzy he induced known as Bacchae. The Romans adopted Bacchus as their name for Dionysus.

- Eleutherios: “The Liberator,” symbolizing his ability to free people from social constraints and self-imposed limitations.

- Lysios: “The one who releases,” highlighting his ability to loosen inhibitions both physically and spiritually.

- Zagreus: In Orphic traditions, Zagreus represents the first-born Dionysus, associated with death and rebirth.

- Bromios: Meaning “the noisy one” or “thunderer,” associated with loud, ecstatic celebrations that came with his worship, and the chaotic energy of nature.

- Dithyrambos: Connected to the dithyramb, a hymn sung in his honor during festivals, symbolizing his role in music, drama, and poetry.

Portrayals and symbols of Dionysus

Earlier images: mature, bearded male, robed, and holding a thyrsus (a fennel staff tied with a ribbon and tipped with a pine cone or artichoke) which represented fertility, prosperity, and hedonism. Dionysus used his staff to punish or reward.

Later images: beardless, androgynous, sensuous youth, often portrayed naked or half-naked.

Popular modern depictions: fat, disorderly man arriving in a triumphant procession with exotic animals. He is often surrounded by maenads and satyrs with erect penises, and sometimes accompanied by the drunken figure Silenus.

Symbols:

- Barrel of wine, grapes, wreath of vines: Symbolising viticulture and wine-making.

- Fig tree

- Panther or leopard skin, symbolizing wildness and primal energy.

- Snake and phallus, representing fertility.

- Bull or bull horns (see why horns were deified)

- Linked to the summer-to-autumn transition and the time of the harvest.

Symbolism and archetypes of Dionysus

Viticulture, seasonal cycle, and regenerative forces of nature: Dionysus is deeply connected to agriculture, particularly grape cultivation and winemaking. His death and rebirth symbolize the cycles of nature. His dismemberment reflects the process of harvesting grapes and making wine, tying him to both the underworld and the vital regenerative forces of nature.

Resurrection: Dionysus is Known for returning from death, Dionysus symbolizes rebirth.

Foreignness: Dionysus is often described as a god who comes from afar, emphasizing his status as an outsider.

Revelry, liberation, and ecstasy: ecstatic states, and spiritual experiences freed his followers from inhibitions, self-conscious care, and social constraints. This liberation was especially embraced by marginalized groups such as women, slaves, and foreigners.

Chaotic, unexpected, dangerous: Dionysus embodies everything outside the boundaries of human reason—he represents both the joy of liberation and the dangers of losing control.

World myth parallels of Dionysus

Liber: The Roman equivalent of Dionysus, Liber is the god of wine, freedom, and fertility, particularly linked to viticulture.

Bacchus: The Roman version of Dionysus, almost identical to him, with similar festivals and rituals.

Sabazius: A deity worshipped in Thrace and Phrygia, associated with freedom and nature, later blending with Dionysian worship.

Osiris: The Egyptian god of the afterlife, rebirth, and fertility, sharing similar themes of death and resurrection.

Zagreus: In Orphic tradition, the first form of Dionysus, representing death, rebirth, and the soul’s journey.

Adonis: A Greek and Phoenician god associated with the cycles of life, death, and vegetation.

Dumuzi (Tammuz): Mesopotamian god of fertility, agriculture, shepherding, and the seasonal cycle of death and rebirth.

Attis: A Phrygian god of vegetation symbolizing death and rebirth, and associated with themes of fertility

Attis: Phrygian vegetation god, symbolizing death and rebirth through nature. Associated with goddess Cybele and shared themes of fertility and resurrection.

Shiva: The Hindu god of destruction and regeneration, often associated with cannabis (bhang) consumption, symbolizing transcendence and spiritual liberation. His dance, Tandava represents both creation and chaos.

Philosophy & literature on Dionysus

Dichotomy between ordered and disordered – Friedrich Nietzsche explored Dionysian concepts in The Birth of Tragedy. He highlighted the intellectual dichotomy between the Dionysian (irrational, disordered) and the Apollonian (rational, ordered). Nietzsche argued that Greek tragedy was shaped by the tension between these two forces.

- He believed that life is a constant struggle between the Dionysian and Apollonian, each battling for dominance but never fully prevailing due to their natural balance. “Wherever the Dionysian prevailed, the Apollonian was checked and destroyed…. wherever the first Dionysian onslaught was successfully withstood, the authority and majesty of the Delphic god Apollo exhibited itself as more rigid and menacing than ever.” And yet neither side ever prevails due to each containing the other in an eternal, natural check or balance”

- Dionysus is seen as the embodiment of the unrestrained will to power.

- Toward the end of his life, Nietzsche went mad, and was known to sign his letters as both ‘Dionysus’ and ‘the crucified’

Suffering as a key feature: Vyacheslav Ivanov noted that Dionysus’s suffering was central to his cult, much like Christ’s suffering is in Christianity.

Jungian psychological interpretation of Dionysus

- Carl Jung, heavily influenced by Nietzsche, discussed the concept of enantiodromia—the idea that anything pushed to its extreme eventually transforms into its opposite. This dynamic is reenacted through inversions Dionysian rituals

- From a Jungian perspective, Dionysus embodies the Shadow archetype, representing the repressed or unconscious aspects of the psyche.

Influence of Dionysus in art and pop culture

Psychoanalysis: The concept of the “Dionysian” has influenced psychoanalytic theory.

Ongoing celebrations: The societal and psychological need for revelry and disorder is evident throughout history (ex; Saturnalia and Mardi Gras), where indulgence includes debauchery, feasting, and hedonism.

J.M. Tolcher’s Poof (2023): Features Dionysus as a symbol of modern liberation, particularly in exploring queer suffering in Australia.

Walt Disney’s Fantasia: Depicts Bacchus in the pastoral segment as a Silenus-like character.

Phallephoria: A modern revival of an ancient Greek festival honoring Dionysus, featuring large phallic symbols, coinciding with Greek carnival season (Apokries) in February/March.

2024 Summer Olympics opening performance: Based on Feast of the Gods, which included Dionysus, painted by Jan van Bijlert.