Quick Facts on the Botticelli Primavera

Artist: Sandro Botticelli

Time period & style: Early Renaissance, Italy. 1480’s

Current location: Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Material: wood, 207 x 319 cm

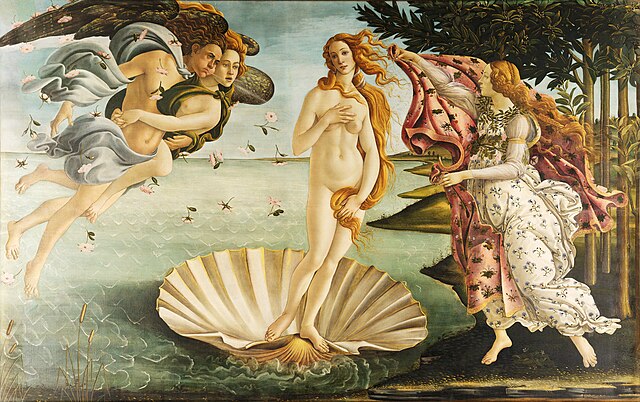

The Botticelli Primavera painting is one of the most popular and discussed Renaissance artworks in the Western world. The reason is its enigmatic composition that no one has satisfactorily decoded, and let’s face it, it is a stunning painting. It features soft, well-balanced colours, and delicate, detailed flowers and clothing. Some parts look a bit creepy, like the flying blue-winged man grabbing a thinly covered, scared-looking girl. Then, there are some calm figures staring in your direction, and a trio of women, also dressed in see-through garments, dancing with calm and pensive faces.

Why did Sandro Botticelli paint the Primavera and for whom?

Though Botticelli’s Primavera now rests in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, it used to belong to the Medici family, arguably the wealthiest family in Italy at the time. The Medici rose in wealth and fame due to textile trade and then banking, but its prominent members were also significant patrons of the arts, philosophy, and science, as well as political figures, such as Lorenzo de Medici. It is said that they commissioned Botticelli for this painting to celebrate the marriage of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco, Lorenzo’s cousin. Some sources say that it also celebrated the birth of a baby in the family.

Analyzing Botticelli’s Primavera painting – elements and figures

Breaking down mythological elements

Going from right to left the 9 figures are:

- Zephyr – The god of the west wind in Greek mythology, depicted with wings. He is one of several wind gods named the Anemoi and is known to be the gentle wind associated with spring

- Chloris – A Greek nymph goddess associated with spring, flowers and new growth.

- Flora – The Roman goddess of flowers and spring.

- Venus – The Roman counterpart of Aphrodite, the Goddess of love and beauty.

- Cupid – The God of desire, attraction, passion, and erotic love.

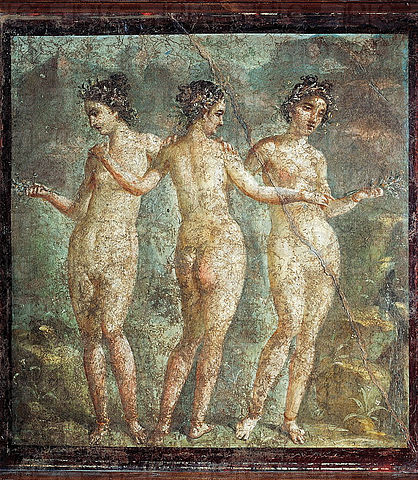

- The Three Graces (or Charities) – Could come in different numbers, but 3 had been eventually established. They represent charm, beauty, nature, human creativity, goodwill and fertility. Their role in myth was to attend to the other Olympians, particularly in feasts and dances. They celebrate or make things more enticing.

- Mercury / Hermes – The messenger god, known for having a caduceus.

There is no single mythological narrative that contains all of these 9 figures. However, it seems that Botticelli took bits and pieces found in classical mythology and put them together to visually express something that clearly surrounds the same theme. For example (still going from right to left):

Zephyr, Chloris and Flora

In Ovid’s Fasti (Book of Days – a treatment of the Roman calendar), Book 5, 2 May, the author describes the ‘arrival of spring’ through an allegory; Zephyr was attracted by Chloris’ naked charm, so he pursued her. As he embraced her, flowers sprang from her mouth, transforming her into Flora, the goddess of flowers. It is said that until then, the earth had been a single colour, likely green, given her name. The Greek word for green is ‘khloros’, which is the root of the word ‘chlorophyll’.

This story is also told in the poem De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things) by Lucretius (1st century) and includes the presence of Venus and Cupid.

“Spring-time and Venus come, and Venus’ boy, / The winged harbinger, steps on before, / And hard on Zephyr’s foot-prints Mother Flora, / Sprinkling the ways before them, filleth all / with colours and with odours excellent.”

Venus and Cupid

Where there is Venus, there is Cupid. They are often seen together in classical art. In Greek literature, Cupid’s parentage is not solid (some say he’s the son of Zephyr and Rainbow, while others say he’s the son of Ares and Aphrodite), but in Latin literature, Cupid is definitely the son of Venus. His father was debated for a while but was later solidified as Mars, where the trio is well known in the allegory of ‘Love and War.’

Cupid is portrayed as a chubby winged baby holding an arrow and torch because ‘love wounds and inflames the heart.’ He is blindfolded because, as Shakespeare explains in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, love isn’t seen with the eyes but felt and understood with the mind. Love doesn’t rely on good judgment or taste. The wings and blindness suggests that love can be impulsive and rushed while depicting love as a child implies it can be easily fooled or misled. Ultimately, the idea is that love is driven more by emotions and feelings than by rational thinking.

Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind and therefore is winged Cupid painted blind. Nor hath love’s mind of any judgement taste; Wings and no eyes figure unheedy haste. And therefore is love said to be a child because in choice he is so oft beguiled

The 3 Graces

The Three Graces were minor goddesses mentioned in Greek mythology, symbolizing celebration, charm, and beauty. For example, after Hephaestus created Pandora, on the orders of Zeus to punish humanity, the Graces placed a golden necklace on her skin (Hesiod, Works and Days). In archaic and classical Greece, they were finely dressed, but later, they were often depicted naked or semi-naked.

Mercury/Hermes

Lastly, we have Mercury, mostly known for being the messenger god holding a caduceus and named Hermes in Greek myths. His representation in this painting seems to be less obvious than the other characters because his attributes don’t quite fit. In myths, he is the messenger god who delivers messages to people and gods, often sent by Zeus. He is also a psychopomp who guides the newly deceased to the underworld. He also represents cunning and trickery, having played tricks on other gods, namely Apollo.

While these representations don’t seem to fit, there is a common trait that might: his swift movement. As a traveling god, he is often mentioned as moving swiftly across the skies (as seen in the Aeneid and Homeric Hymns). In the painting, he’s shown with his caduceus pointing at the clouds, as if he’s parting them to make room for the spring. Additionally, Hermes was one of Aphrodite’s lovers and fathered a child with her, though he was not her only lover, given she is the goddess of beauty. This story might have been conveniently used to include Hermes in the scene, perhaps suggesting that he must make way for the beauty of spring to arrive?

Other symbols and motifs

When you look longer, you’ll notice that these women all have very rounded stomachs, almost almost as if they are pregnant, especially the one in the floral dress. To make sure this isn’t simply the style of the artist, Sandro Botticelli, I looked at his other paintings such as The Birth of Venus, Venus and Mars, The Mystic Nativity, and the Castello Annunciation.

Unless they’re wearing garments with excessive fabric (see Cestello Annunciation), the female figures don’t appear to be at any stage of pregnancy. This wouldn’t be surprising for the Primavera painting, as it is a painting created to celebrate the union of two people or a birth. That could explain why it’s called Primavera, meaning ‘spring’ in Italian, as spring is the season of fertility and birth. However, it’s worth noting that the name was only given to the painting 70 years later by another artist and art commentator, Giorgio Vasari.

Meaning interpretation of the Primavera

The consensus among the art world is that Botticelli’s painting is about springtime (Primavera), due to the story of Chloris and Zephyr, which explicitly allegorizes the season. The other figures also add qualities to the season— Venus for its beauty, the Graces to celebrate or beautify the weather, and Hermes clearing the skies. However, the painting remains a bit of a mystery, and there are ongoing discussions about its deeper meaning and message. For example, the art historian Kenneth Clark interprets the painting as “the three graces of spring.” Others highlight the notion of sensuality. After all, Botticelli chose to combine mythological figures together to convey a certain message he had in mind.

I personally think it has to do with celebrating the union of love resulting in fertility. Botticelli was commissioned to create a piece celebrating a couple getting married and expecting a child. He pieced together symbols of this celebration, with Venus perhaps representing love at the center, and the movement into fertility as a result of a union of love. But that’s my interpretation of the painting.

The subtleties in meanings are plentiful: the beauty of fertility, the beauty and mystery of fertility, the beauty of spring, the relationship between women and spring, the celebration of fertility, and the celebration of love and its union resulting in fertility. That’s the mystery of the Primavera. That’s the mystery of art.